Market Comments

“No warning on earth can save people determined to grow suddenly rich.” —Lord Overstone

When newspapers and reporters declare the stock market is up or down due to a specific event or piece of data, the editors are simply creating a narrative to produce a headline. A narrative is a story or line of reasoning that helps explain an event. Sometimes a narrative can be factual, but narratives are often fabricated in order to fit an otherwise unexplained reality. By nature, humans seek narratives—we want control and the comfort of understanding. Of course, trying to condense millions of investment decisions into one headline is not only silly, it’s misleading.

To download a PDF of this report, click here.

In recent years, an ever-changing narrative helped market participants justify investing in an expensive market. A common recent theme: “bad news is good news.” The stock market often moved higher with the release of economic reports showing weak growth. Rather than link weaker economic growth with weaker earnings and inevitably lower stock prices, the narrative comforted investors with the belief that the U.S. Federal Reserve stood ready to counteract a weak economy with monetary stimulus, consequently pushing stock prices higher regardless of fundamentals. The narrative provided investors reassurance and a rationalization to continue buying stocks despite extreme valuations and stagnating growth.

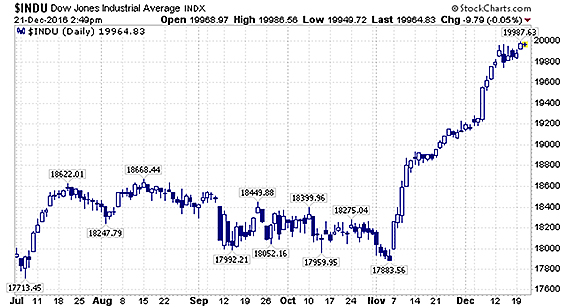

Immediately following the U.S. elections in November, the Dow Jones Industrial Average index exploded to a new record high. Within several weeks of the election, the S&P 500 index, the technology-heavy Nasdaq index, and the small company Russell 2000 index all followed the Dow Jones lead, and achieved new all-time highs. To place these milestones in perspective, the last time this happened was on the last day of December in 1999. Investors are clearly bullish, as the new narrative suggests Trump’s policies will be good for stocks. With the surprise Trump election victory, the market responded to a significant change in the narrative. Overnight virtually every major trade was turned on its head.

The new narrative implies that Donald Trump will cut taxes, increase infrastructure spending, reduce regulation, allow for the repatriation of foreign corporate profits, along with a host of other business friendly ideas. All of these proposals were publicly known weeks before the election, when the market sold off on concerns Trump might win the election and his administration would bring uncertainty. Out of desperation for answers to the market’s unexpected rally, the narrative was quickly changed.

The new narrative is bullish for companies like heavy equipment manufacturer Caterpillar, as CAT stock jumped 12% immediately following the November election results. Although Caterpillar is suffering through its third year of top-line revenue declines, traders quickly embraced the new narrative and pushed the company’s stock immediately higher. Following the company’s latest earnings release, Caterpillar has now failed to record positive revenue growth for forty-eight consecutive months. Further, a quote from a Caterpillar executive attempts to temper the enthusiasm and set more realistic expectations: “Even if you step back and thought about when we would start to see some impact from any sort of infrastructure program, I think the best case scenario you are talking about late 2017. It takes some time for large infrastructure projects, for the funding to come in, for the projects to be planned, and for the equipment to be delivered.” Regardless, traders are quick to get in the cart way before the horse has even left the barn.

Distracted by rising stock prices, investors have largely overlooked the sharp sell off in the bond market, which is pricing Trump’s proposed policies as highly inflationary. Unanswered questions remain about the new administration’s ability to fund its infrastructure investments with less expected revenue from the anticipated tax cuts. The obvious answer is by issuing more debt — but the numbers are concerning. The Tax Policy Center estimates that Trump’s tax plan will increase the federal debt by $6.2 trillion over the next ten years. Add the proposed $1 trillion infrastructure plan and the amount of additional debt layers on the already sizeable $20 trillion in U.S. federal debt. As higher interest rates will only increase the cost of annually servicing this growing debt burden, the logical question becomes how high can yields rise before they inhibit economic growth? Never to be deterred, the equity market continues to march relentlessly upward. Investors who once fled the market, whether fearing expensive valuations or the dread of another sharp downdraft in stock prices, have now returned with a vengeance.

Conducting a simple online search, there are evidently bubbles in real estate, bonds, technology, venture capital, stocks, shale oil, healthcare, the US dollar, college tuition, Canadian housing, central banks, social media and China. We read a recent article where one economist simply said “Everything’s a bubble.” Yale University economist Robert Shiller noted that the word “bubble” was not even in the economic lexicon twenty-five years ago. Meaning, one could not find the word “ bubble” in any academic textbook or paper. Yet today bubbles apparently exist everywhere according to google search.

Robert Shiller, in his book Irrational Exuberance, tried to develop a checklist of bubble symptoms. His criteria included rapidly increasing prices, media cheerleading, and popular stories about how much money people are making (along with envy and regret among those sitting out the bubble). Shiller’s efforts were far from perfect—a lot of characteristics can satisfy elements of the checklist. As a result, an asset class labeled a “bubble” by some may simply be expensive and beholden to the regular cycle of capitalism.

Cycles are self-reinforcing and one of the most fundamental parts of a healthy market. If asset valuations never became expensive, they would always offer attractive investment returns. Thus, the very existance of attractive investment returns attracts capital, which in turn makes assets expensive. Of course, expensive assets attract less discerning capital and prices fall. This simple loop explains why cycles are ever-present in an open market with free-flowing capital.

In contrast, a bubble exists when the cycle breaks downward but attractive investment returns do not materialize after prices fall. Hence, the asset class offers no hope of recovery and the entire investment premise disappears. This was certainly the case with many technology dot-com stocks in the late late 1990s (think pets.com), which still offered no tangible investment prospect after their stock prices dropped 90%. This was also true of the the often referenced tulip bubble in 17th century Holland, as well as the South Sea bubble.

The South Sea Company, founded in 1711, was an unusual business. The British government promised the company a monopoly on trade with Spanish South American colonies in exchange for taking over England’s national debt incurred during the War of Spanish Succession. Unfortunately, the trade concessions turned out to be less valuable than anticipated. In January 1720, when the company’s shares traded at £128, the company directors circulated false claims of success and stories of South Sea riches. By February, company shares had risen to £175. The following month the company convinced the government to allow it to assume more national debt in exchange for its shares. With investor confidence growing, the share price climbed to £330 by the end of March.

The South Sea Company was part of a wider trend in stock speculation at the time. Newly created trading firms with similar characteristics appeared, intent on attracting easy capital. Such was the euphoria that 1720 was known as the “bubble year”. The South Sea Company, in a successful attempt to prevent other bubbles from diminishing its own importance, encouraged Parliament to pass the Bubble Act in June of that year. The South Sea Company received its charter under the Act, perceived as an official vote of confidence in the company, and by the end of June the company’s share price peaked at £1,050. Shortly thereafter, investors started to lose confidence and by September the shares plunged to £175.

Even Sir Isaac Newtwon, Britain’s most celebrated scientist, bought in to the South Sea Company. Newton profited nicely from his investment. After selling his interest, Newton then watched with envy as stock in the company continued to rise. Newton decided to repurchase an even larger stake in South Sea Company shares, now valued at more than three times the price of his original investment. Within six months, Newton lost £20,000, or £3m in today’s terms, which at the time amounted to his life savings. Newton allegedly said that “I can calculate the movement of stars, but not the madness of men.”

Although bubbles should be avoided, as one risks the permanent loss of investment capital, assets with a valuation above historic average are not always bubbles. As a result, cycles are not to be avoided—cycles simply necessitate that one be patient to earn long-term returns. Cyclical excesses eventually correct, recover, and the capital is once again redeployed. This important distinction between bubbles and cycles determines how one invests and responds to market gains and losses.

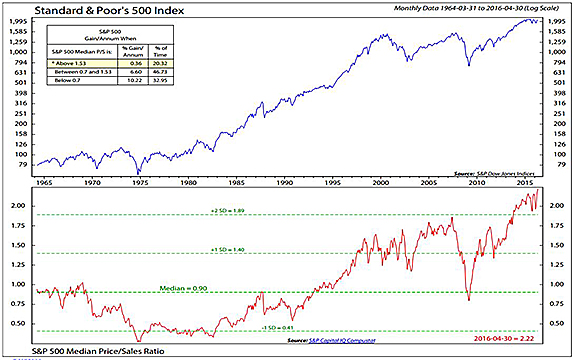

The current market cycle is at a point where we believe valuations are expensive, as the median stock has never been more overvalued on a price-to-sales basis. Of course, corporations could grow into this valuation, but this can happen only through (1) sales growth or (2) the expansion of profit margins. Given today’s valuation levels, corporations probably need to do both to justify current market prices.

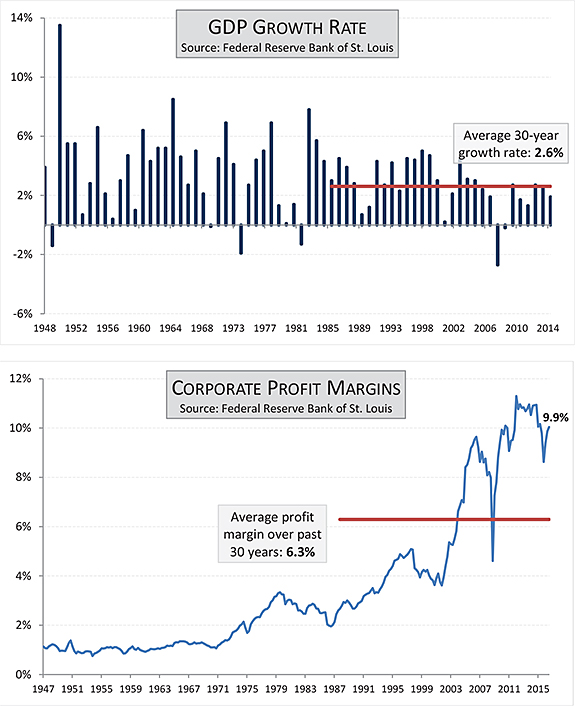

Sales growth often comes from an increase in demand. Trump’s targeted fiscal stimulus and infrastructure spending might create demand, but not as a sustainable source of rising growth. Sales growth can also come from inflation, but the trouble with inflation is that it hurts profit margins (higher cost of goods and labor) as well as dampens valuations (higher discount rates). The normal source of demand comes from consumers; however, consumers have already taken advantage of generational low interest rates to releverage their balance sheets, buying cars and houses with cheap capital. With both long-term and short-term interest rates rising meaningfully post-election, we doubt that the economy will repeat the same level of credit-financed consumption as that of the past eight years. In short, future sales growth looks tepid.

The other opportunity for corporations to grow into their valuations is by expanding profit margins (although we would note that wider profit margins in no way reduce the stock market’s record high price-to-sales ratio). Corporate profit margins have recently begun to fall lower from record highs. Historically, profit margins are one of the most mean-reverting series in finance. As such, profit margins could stagnate, at best, or potentially fall dramatically back to the mean.

In our opinion, two major forces stand behind the expansion in profit margins over the past decade: interest rates and globalization. Falling interest rates acted as a tailwind to profits by lowering the cost of capital. This tailwind looks to have ended and could easily become an impediment. Globalization allowed American companies to reduce their labor and production costs through outsourcing and offshoring. The Trump administration’s proposed policies may now weigh against the globalization trend. The prospects for U.S. corporations to grow into their extreme valuations by expanding profit margins looks weak. In fact, a better argument can be made that profit margins now face considerable headwinds and will likely compress current valuation multiples.

The new, post-election narrative embraces Trump’s promised market deregulation, tax cuts and infrastruce spending in order to justify the stock market’s surpising year-end surge. Just as Sir Isaac Newtown changed his opinion based on rising prices, so too have the Wall Street strategists. David Kostin, chief strategist for investment bank Goldman Sachs, remained cautious throughout 2016 based on his concern for the market’s expensive valuation, which is no longer his position. With rising oil prices and the S&P 500 index at all time highs, Kostin finally threw in the towel. Following Trump’s victory, Kostin wrote in a recently published report that the Trump “hope” will dominate and the S&P 500 should rise to 2400 in the first half of 2017. Not to single out Kostin, but “hope” is never a viable investment strategy.

There are many factors to consider before bluntly assuming the new administration’s plans as significantly positive. Although a popular narrative compares Trump’s economic policy proposals to those of Ronald Reagan, we caution that the economic environment and potential growth in 1982 was vastly different than today.

Reagan inherited a stock market priced at cyclical lows that made it hard to lose if one invested in stocks. The S&P 500 offered a 5.7% dividend yield at a multiple of 7.4x earnings, while U.S. government bonds, maturing in ten years, yielded 15% and were headed lower. The market was clearly in a diffent stage of the cycle when Reagan took office.

Investors should always recognize the popular narrative and respect it as a formidable short-term force driving the market. That said, investors must also judge the logic behind the narrative. In the late 1990’s investors bought into the new economy narrative fueled by dramatic technological advances. By 2002, investors painfully learned that the narrative was mostly built on greed. Similarly, mid-2000’s real estate investors contended that real estate prices could never decline. Of course, the losses of 2008 provided a sobering dose of reality.

The bottom line is that investors should respect the narrative and its ability to drive markets temporarily. However, independent thought is necessary to accurately understand the pros and cons of Trump’s proposals, as well as the daunting odds of enacting them. One’s investing success is dependent on determining whether the narrative is logical, or simply a rationalization to provide the comfort and control investors desperately seek.

Nobody thought a Trump victory would happen, but it did. Nobody thought “Brexit” would happen, but it did. Despite all of the market’s gains in the last two years only ocurring after the November election, Wall Street pundits all foresee a higher stock market for the next year and beyond. However, the post election rally is a speculative guessing game, as people are wagering on the effectiveness of Trump’s economic policies before he has even taken office. The reality is that no one invested in the market has any idea what will actually happen. The only sure bet is that the narrative will change to fit the story.

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHY

“Complexity is not intelligence”—Michael Lewis

Investor Warren Buffett has often said, “I could improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only twenty slots in it so that you had twenty punches – representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime. And once you’d punched through the card, you couldn’t make any more investments at all. Under those rules, you’d really think carefully about what you did, and you’d be forced to load up on what you’d really thought about. So, you’d do so much better.” Buffett is correct—this approach would be a powerful way to manage an investment portfolio.

Many investors call themselves Buffett acolytes but few, if any, actually measure up against the twenty-punch card test. Even Warren Buffett’s two hand-picked successors, Todd Combs and Ted Weschler, have turned over many stocks in the past few years, at prices that we cannot reconcile with the twenty-punch-card philosophy. Human nature prevents most investors from meeting the twenty punch-card test—it is difficult to be patient and a twenty-punch card investment portfolio is, by its nature, a concentrated investment portfolio.

We find it interesting that when making investments, individuals act dramatically different than when shopping for other goods. For example, when shopping for groceries, the consumer methodically goes through the store with a specific list of needed items for purchase. The shopper is value conscious and, when an item is on sale, will likely purchase an additional amount at the margin. By contrast, when stock prices fall, the general reaction is fear—the opposite reaction to lower prices in a store. Further, most stock shoppers buy a little of everything, regardless of value. The average equity mutual fund owns 90 stocks1 — and an index fund is a collection of every item in the store. While groceries rarely go back to the store, the same cannot be said about stocks, where turnover, or the percentage of a fund’s holdings that change every year, averages 85% according to Morningstar.

The intelligent investor should behave like the rational consumer: research and decide on the few businesses that are worth purchasing. Then only buy these stocks when on sale. When these conditions do not prevail, sit on the sidelines until they do. To wait with cash and have patience is not easy, but it is rational. Unfortunately, in the investing world today due to the cycle, there are few bargains in the equity store (despite the prevailing narratives).

The basics of investing are really about common sense. Yet, over time, few investors grasp these basic ideas or they lack the discipline to implement these actions. By constantly reinforcing and refining these concepts, investors can improve their odds of long term investment success.

With kind regards,

Robert J. Mark

Portfolio Manager

The opinions expressed are those of the Fund’s portfolio manager and are not a recommendation for the purchase or sale of any security.

The following indices, composites, averages and theories referenced in this commentary are defined as follows by Investopedia: The Nasdaq Composite is a market-capitalization weighted index of the more than 3,000 common equities listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange. The Dow Jones Industrial Average is a price-weighted average of 30 significant stocks traded on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the NASDAQ. The Russell 2000 Index is an index measuring the performance of approximately 2,000 small-cap companies in the Russell 3000 Index, which is made up of 3,000 of the biggest U.S. Stocks. Mean reversion is the theory suggesting that prices and returns eventually move back toward the mean or average.

As of December 31, 2016, the Fund does not own any of the following securities mentioned in this letter: Caterpillar, Inc.

The Fund’s investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses must be considered carefully before investing. The prospectus contains this and other important information about the Fund, and it may be obtained by calling 1-877-743-7820, or visiting www.castleim.com. Read it carefully before investing.

Performance data quoted represents past performance; past performance does not guarantee future results. The investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate so that an investor’s shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Current performance of the fund may be lower or higher than the performance quoted. Performance data current to the most recent month end may be obtained by calling 1-877-743-7820.

The risks associated with the Fund, detailed in the Prospectus, include the risks of investing in small and medium sized companies and foreign securities which may result in additional risks such as the possibility of greater price volatility and reduced liquidity, different financial and accounting standards, fluctuations in currency exchange rates, and political, diplomatic and economic conditions as well as regulatory requirements in foreign countries. There also may be risks associated with the Fund’s investments in exchange traded funds, real estate investment trusts (“REITs”), significant investment in a specific sector, and nondiversification. Technology companies held in the Fund are subject to rapid industry changes and the risk of obsolescence. The Fund is non-diversified, meaning it may concentrate its assets in fewer individual holdings than a diversified fund. Therefore, the Fund is more exposed to individual stock volatility than a diversified fund. Distributed by Rafferty Capital Markets, LLC-Garden City, NY 11530.

Comments are closed.